Trailblazers: The Yukon Agreements are charting a path to reconciliation

For Robin Bradasch, a citizen of the Kluane First Nation, the word reconciliation carries a lot of meaning and has for a long time.

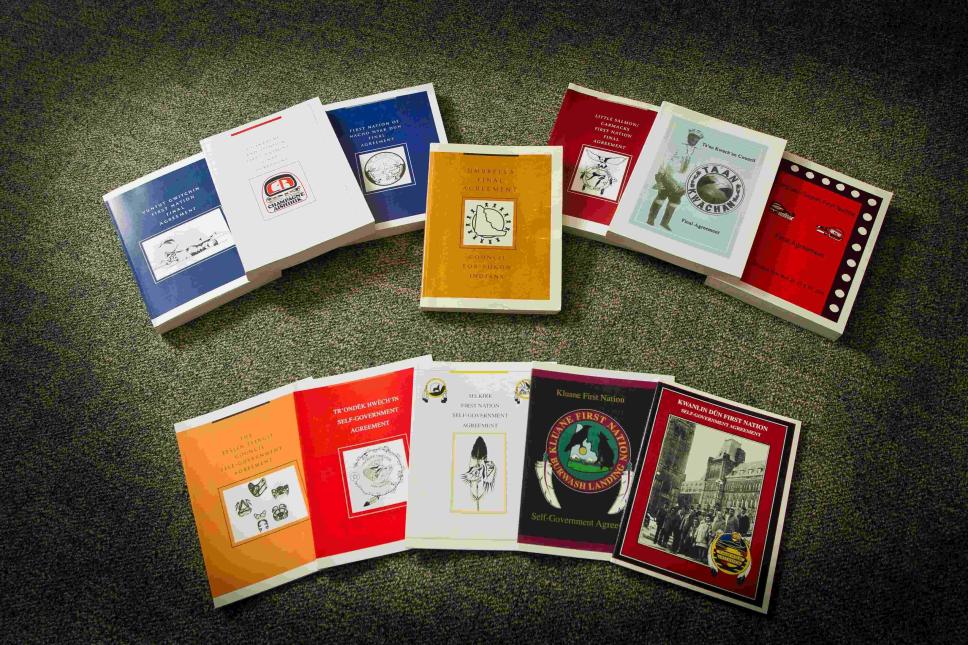

In Yukon, 11 Yukon First Nations have signed land claim and self-government agreements with the governments of Yukon and Canada.

These agreements are negotiated settlements around how Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and governments will live and work together in Yukon – they form a critical aspect of reconciliation in the territory, and in Canada.

Bradasch remembers being a negotiator for Kluane First Nation’s Final and Self-Government Agreements. For her, working on the Agreements became a way of life. Bradasch was a negotiator for 12 years for her First Nation, and has since been working in implementation for over 10 years with the federal department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs.

Reconciliation is about restoring friendly relations, it’s about restoration of balance and righting wrongs.

Yukon First Nations are resilient people. They faced a complete destruction of their way of life “from the building of the Alaska highway to residential schools, its trauma after trauma. They only gained the vote in 1960 and 13 years later, they were the first in Canada to think through a comprehensive land claim document,” Bradasch says.

The landmark Together Today for our Children Tomorrow document presented by Yukon First Nations to the Prime Minister of Canada in 1973 set out a framework for land claims and self-government and served as a vision to make Yukon a better place for everyone.

With a lot of hard work behind the agreements, today a different way of thinking is influencing government and society. “Do we really need to battle it out over every sentence [in the Agreements], or can we come together…that’s starting to shift,” Bradasch says.

Self-government 2.0 - Restoration of Self-Determination

The Yukon land claims and self-government agreements are rooted in the idea of putting decision-making power back into the hands of First Nations and their communities, Bradasch says.

“These agreements have always been rooted in that idea of trying to recognize something that was already there and bring it back,” Bradasch says.

Brian MacDonald, a citizen of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, is the Assistant Deputy Minister of Aboriginal Relations for the Executive Council Office of the Government of Yukon. His responsibility is to provide advice on how Yukon government departments can work together with Yukon First Nations.

I believe that the First Nations have always been governments. They’ve always governed themselves; they’ve governed their lands and their resources… all these agreements are doing in my view is recognizing what already existed.

Partnership

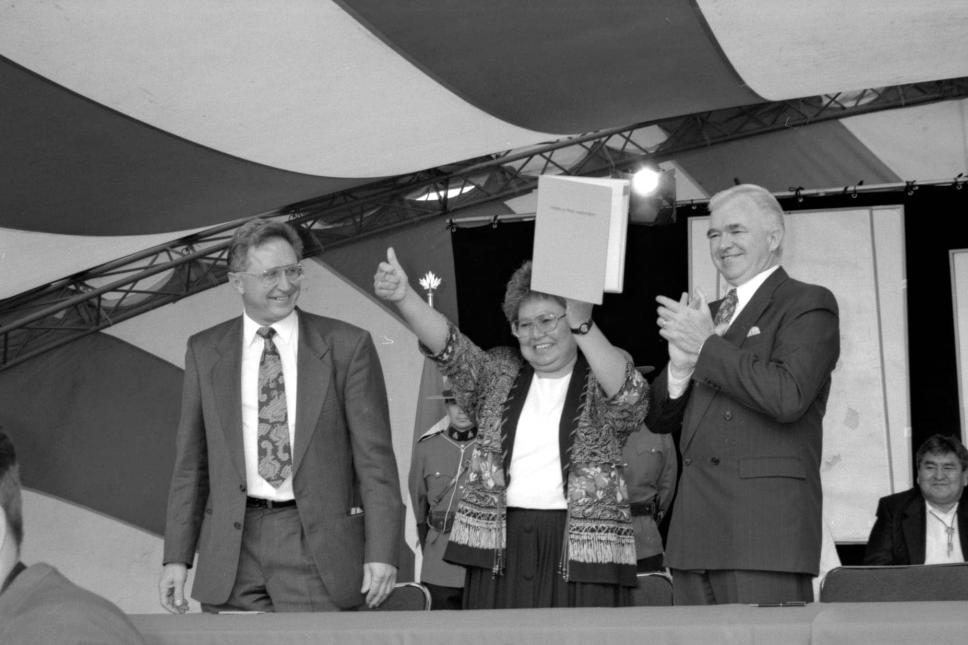

Judy Gingell, respected community leader and former Chair of the Council for Yukon Indians, now the Council of Yukon First Nations, says she experienced reconciliation on a personal level during her involvement in the negotiation of the Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA). Before the UFA, laws were imposed on her as a First Nations person.

“Working through these Agreements was a real plus for me as an individual. It helped me to address a lot of the anger and the hurt, and to clearly understand what really happened to our people. To be able to have the opportunity to fix it through these land claims agreements; to me that is a sign of reconciliation,” she says.

Our agreements are all about partnership.

Partnership wasn’t always the norm in Yukon. “We were always left in the back. We were never a part of what was going on here in the Yukon. But now, we all have to work together. We all have to make it work,” Gingell says.

“There are processes under the Agreements that identify how we can work better as neighbours, but also how we can work effectively as partners. You see that throughout the land claim,” MacDonald says, citing the boards and councils that manage wildlife and resources, and conduct land use planning and environmental assessments. All Yukoners have guaranteed opportunities to participate in these advisory bodies.

“That was premised on the principles of Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow,” MacDonald says.

Celebrating Diversity

“The success of reconciliation is based on the willingness of all Yukoners to support and appreciate the diversity of culture that is the Yukon,” says MacDonald. “The land claim is an incredible step forward for reconciliation, it is a cornerstone to how we’ve been able to move forward and build awareness of the various cultures. It prevents the marginalization of Yukon First Nations.”

Moreover, Yukoners are now celebrating First Nations culture through events such as the Adäka Cultural Festival, and there is growing interest in First Nations cultural centres.

“These are all celebrations of First Nations culture that have been embraced by Yukoners because they see the value and want to have that diversity, that has been a true test of where the spirit of reconciliation has led us in the Yukon,” MacDonald says.

Council of Yukon First Nations Grand Chief Peter Johnston says the Agreements bring culture and traditional forms of governance together with western forms of governance.

We definitely have to have our culture and history in one hand, and in the other hand we have to have a broad, global perspective on everything else.

"We have the best of both worlds and it’s very important that our younger generations grow up with that appreciation for both sides,” the Grand Chief says.

Deconstructing Colonialism

From the federal perspective, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister responsible for Treaties and Aboriginal Government for the Department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Joe Wild, says that recognizing the rights of Yukon First Nations and working as true partners is what reconciliation is all about.

For me, reconciliation is about deconstructing colonialism.

Whether that means creating a new reality through modern treaty-making that isn’t based on colonial underpinnings such as the Indian Act, or simply making space for strong relationships, governments with the ability to evolve over time is key.

“The Yukon is the largest area in Canada where we’ve got self-government working. We hope that they are modelling for the rest of the country, how self-government can work and what it can look like. In that way, the Yukon is at the forefront of reconciliation,” he says.

“The Yukon Agreements are demonstrable models of what a relationship could look like when it is designed together by the parties as opposed to imposed by one party on the other,” Wild says.

Figuring out shared interests and finding new ways of looking at and writing government policy is one ingredient in re-setting the relationship. Respect for First Nations governments - as governments - is the first step.

“The starting position of the federal government is better informed by the Indigenous perspective and the real-life experience of the self-governing First Nations, and involves those First Nation governments as governments,” Wild says.

“We’re designing policy together,” Wild says.

The New Normal

Today, Yukon’s agreements represent a way of life. They create a governance landscape that necessarily involves First Nations in a rich and meaningful way. They guide relationships between citizens and governments and help contribute to reconciliation in our society.

“There is recognition and acknowledgement that there are Aboriginal governments, and they have a say in how we do things…it’s just a way of being,” Bradasch says.